*Notes: 1. As always, the videos won’t play if you read the email version. Follow the link to the blog site to see it all and view the videos. 2. I have to do the whole blog on my phone on this trip, so fingers crossed that it is readable. Xo, Laura

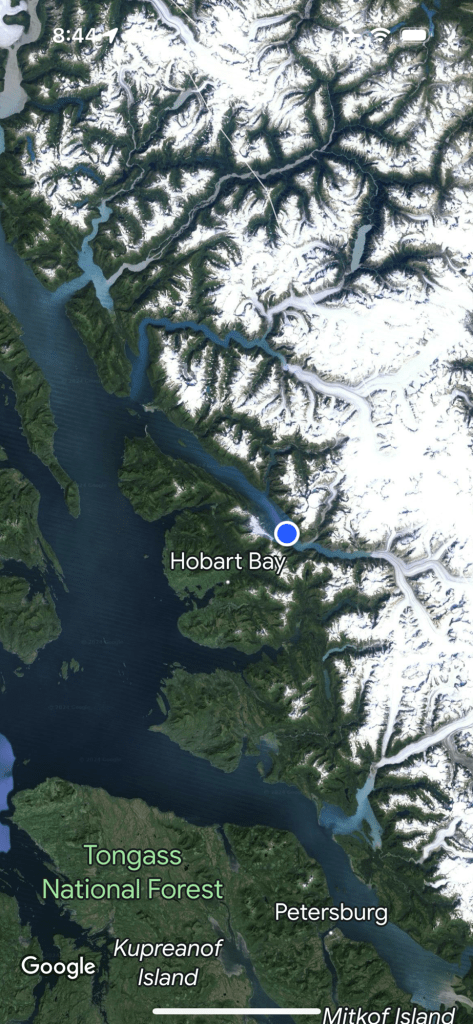

The landscape of the Inland Passage—it’s all about glaciers. Ice rivers thousands of years old, cutting through mountains, grinding them into boulders and ultimately sand and silt, scraping it all along its path, melting, freezing, dragging more rocks and mud, flowing inexorably downhill until they melt, then continue to flow to the sea. Ice fields farther inland feed the glaciers.

Tidewater Glaciers

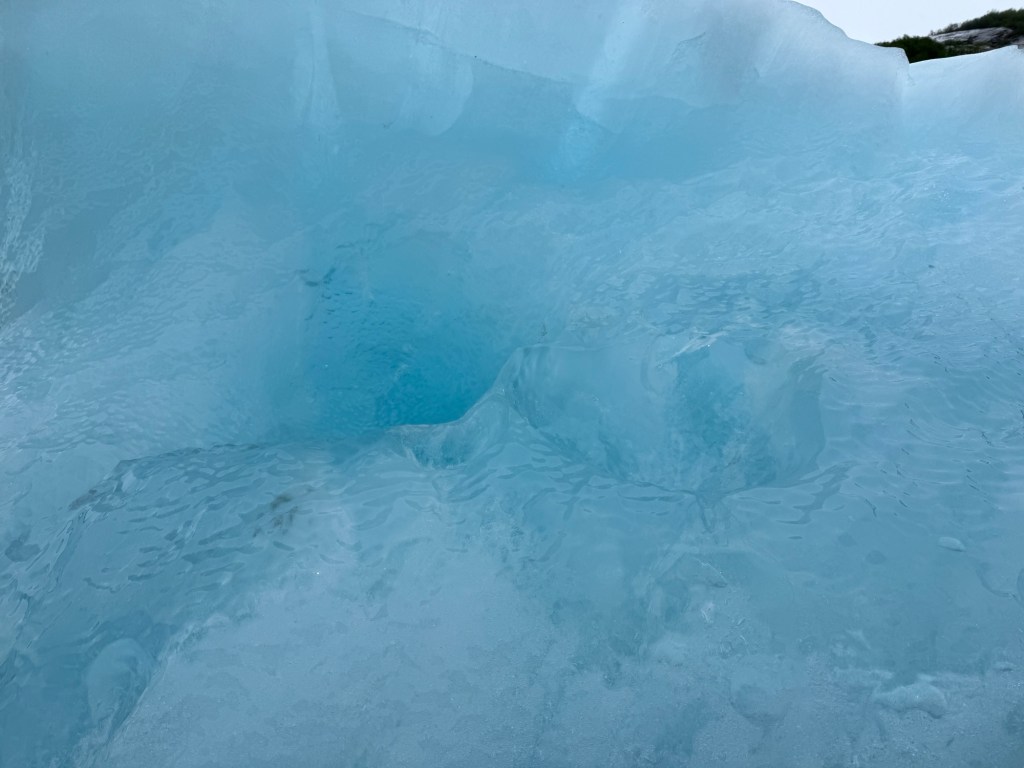

The glaciers that people pay thousands of dollars to see are tidewater glaciers— those that are still floating. The transition from river of ice to inland sea is dramatic. A 300-400 feet of visible glacier may hide another 800 feet of ice floating below the surface.

When it melts, ice bergs “calve” off the face. As they float with the current, ice chunks melt into infinite, ever-changing figures sculpted by mother nature.

Dressed for Success

On the day we loaded into Zodiacs to travel up the Endicott Arm to the Dawes glacier, we donned every layer we had. The 38-degree cloudy morning had evolved into a 38-degree rainy afternoon.

Starting from the toes and moving up: 2 pairs of socks, knee-high heavy rubber boots, thick tights, rain pants, snowboarding pants, an undershirt, a fleece, two rain jackets, a neck gaiter, two ear bands and a knit cap to wear under both hoods, and inner and outer gloves.

And a life jacket. I could turn my head, but barely 😅.

We traveled up to 20 miles an hour, depending on the obstacle course of floating ice chunks.

From Seeing to Feeling

As we sat on the rubber tubes of the zodiac, close enough to the water’s surface to touch ice bergs (I did!), to dip a foot (I did not!), I felt a profound awareness of the contrast between the state of separation from the raw elements of nature afforded by the warm, dry ship and this experience of closeness to those elements.

The container formed by my clothes and the zodiac saved my life, but it was a thin container by contrast to the ship.

Before the cold, windy ride through the rain and ice chunks, the glacier had been an object of awe-inspiring visual beauty and intellectual interest.

From the icy water, as I looked up, I felt the glacier—in my body, my heart, my spirit. Its coldness became a mundane concern of a puny human. What I felt was its power, its force, its inexorability, its massive hugeness as energy in motion.

Hanging Glaciers and the Forests below Them

As glaciers flow in their frozen state, they rise, fall, expand, recede, turn, meet others, always crushing rocks and picking up silt. Gray lines of crushed rock trace the meeting points of multiple glaciers.

Some recede enough to leave paths in the form of giant mountain saddles between cliffs and peaks. “Hanging glaciers” melt from high up.

In the saddles, lichen, then blueberries appear in a few years. Alders, considered the “weed” of trees by locals, start spreading in 10-20 years, then spruce, cedar, and hemlock appear over the next few decades.

After hundreds of years, a dense rain forest evolves, its floor a thick, soft carpet of moss that covers tree roots and fallen logs. Deer cabbage, skunk cabbage, salmon berries, devil’s club, and a host of other plants take root.

The Tlingit peoples continue to put many of them to use as foods and medicines.

Muskegs

When glaciers leave flat valleys of silt behind, mosses begin to grow, then grasses and small plants. Annual cycles of precipitation and continued plant growth ultimately form a 40-200 feet deep spongy, watery bog, a “muskeg.” They are acidic, so few trees form.

Beavers love muskegs! They build huts to live in and dams to form ponds. Locals ice skate on them in the winter. Muskegs that are too watery make trouble for deer and moose hunters, who like to be able to walk through them.

In the best of conditions, muskeg walking requires tall boots and strong legs. As you stand, you slowly sink.

Houses built on muskegs stand on one or two dozen pilings drilled up to 200 feet. One of our guides came home from work one day to find that the floor was tilted and the doors didn’t fit…the muskeg had shifted.

(We didn’t ask what she and her husband were going to do about it. She was 36 weeks pregnant and they were ready to head to Ketchikan where there is a doctor as well as a midwife.)

Keeping Spirits Up

About 3 miles into our 7-mile Zodiac ride in the rain, our driver cut the engine without warning. Suddenly another Zodiac zoomed toward us. One rider had a Viking helmet on. Pirates??

No!

Spirits!

Bailey’s Irish Cream, Crème de Minthe, and hot chocolate. Ohhhhhh!!!!

Amy had hot chocolate, I had The Works, the gentleman across from us had “just the booze”—a first for the guide.

This welcome surprise is just one example of the exceptional service offered on our Lindblad/National Geographic expedition.

Leave a comment