Prologue

The Sun Dagger, ca. 1985

Fajada Butte towers over Chaco Canyon in northern New Mexico.

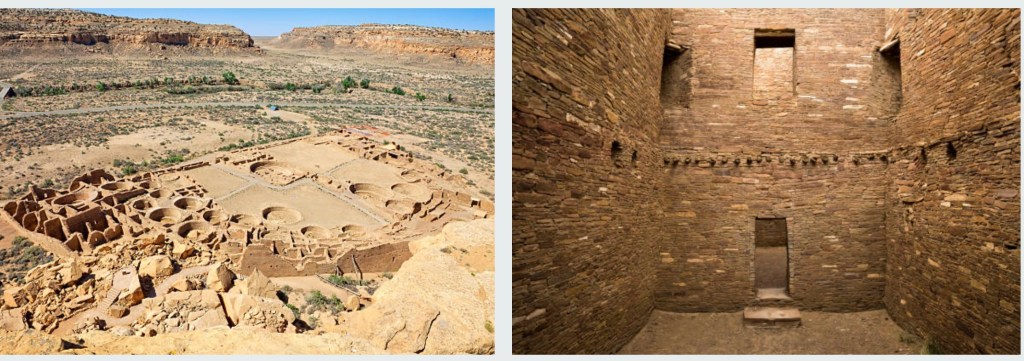

Centuries ago, the Anasazi (Ancestral Puebloans) built an enormous, multi-level complex on the canyon floor, piecing together thousands of sandstone blocks. Now called Pueblo Bonito, the great house covered around 3 acres, and is estimated to have been 4-5 stories high and contained ~700 rooms and ~35 kivas (round ceremonial rooms).

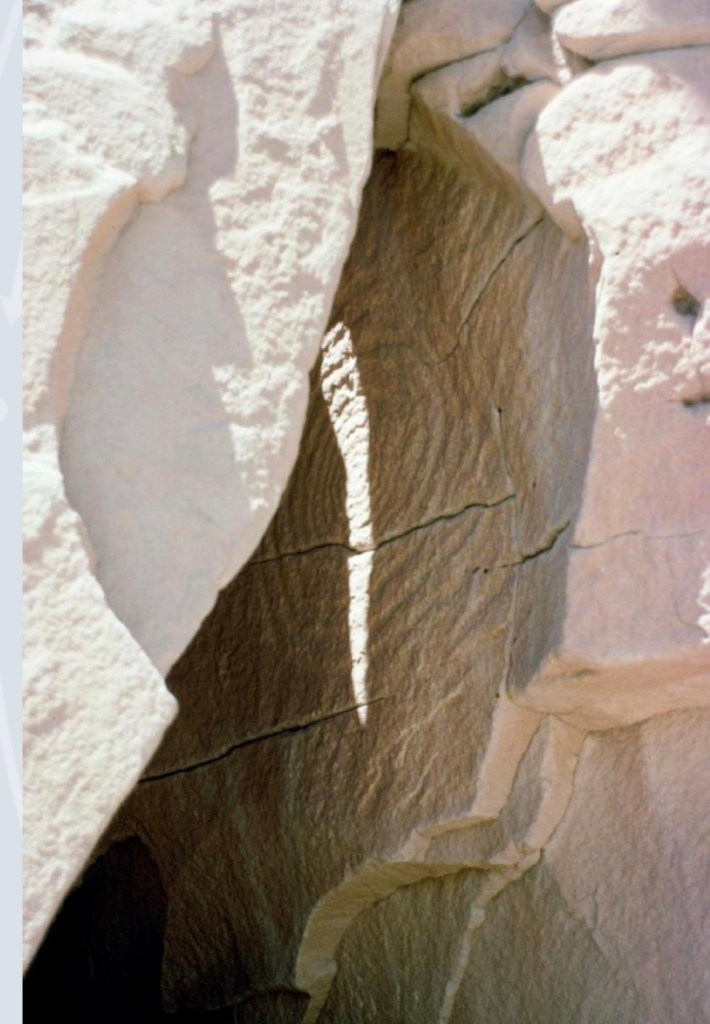

On my first visit to Chaco Canyon a booklet in the Visitor Center caught my eye—The Sun Dagger. Its cover featured this intriguing photo.

The rock carvings that created the Sun Dagger are hidden off a faint path near the top of the butte. The Ancient Ones had etched a large spiral to mark where a streak of light shone on the rock face.

The Dagger bisected the spiral at the summer solstice. At the winter solstice, two light daggers perfectly bracketed the large spiral.

Just to the upper left side of the large spiral (not visible in this photo) is a smaller spiral, where light daggers pierced the center at the spring and fall equinoxes.

Given the timing of my visit, I did not witness the perfect alignment of the solstice. Nonetheless, I was enthralled in a way I can’t explain—with the patience, brilliance, and reverence the Anasazi brought to their perfect measurement of the movement of the sun.

The carvings survived many centuries beyond the mysterious disappearance of the Anasazi. Sadly, the rock formation shifted in 1987 (likely due to the pressure of visitors such as myself), and the Dagger no longer pierces the heart of the spiral. The site is now closed to visitors.

How fortunate I was to see it and touch it.

If I had any earlier knowledge of indigenous sun markers, I don’t remember it. The Sun Dagger sparked a life-long fascination with these ancient observers of the sun and a curiosity about the meanings behind them.

(For more on the Sun Dagger, look up scientist Anna Sofaer.)

Machu Picchu, Peru 9/23

> The Intihuatana Stone

An early morning hike led us toward our primary destination, the famous Sun Temple. Before we reached it, we passed a stone cut into the form of a squat square pillar.

The pillar stands slightly askew–its angle seemingly at odds with the precise stonework in this sacred upper area that was reserved for the Inca elites, whose capitulations to the gods governed plantings, harvests, and other rituals.

After Hiram Bingham alerted the world to Machu Picchu in 1911, he and others discovered (among many other things!) that at the spring and fall equinoxes, the Intihuatana stone casts no shadow.

To make that happen, the Inca had to carve the stone such that its angle matched the latitude of Machu Picchu: 13 degrees south. The tilt of the stone was purposeful…and to my mind, close to magical!

My jaw dropped into yet another “wow,” and I took a moment to gaze in wonder, again, at the genius of the people who built this city in the sky.

> The Chakana, or Andean Cross

The Andean Cross symbolizes the three-part world of the Inca and other indigenous peoples of the Andes.

The upper sphere is occupied by the gods, the lower sphere by the ancestors who have passed on, and the middle sphere by the living. Steps up and down on both sides mark pathways between worlds and represent cycles of life.

As you approach a large stone near the Temple of the Sun, you can see it is carved into the shape of the chakana—but only the top half appears above ground.

Is the bottom half buried to separate the underworld from the here and now? That’s what we conjectured. But no—this stone is another monument to the reliability of the sun.

As the earth revolves around the sun, the image of the underworld slowly appears, completing the chakana icon at the solstice. On the left side of the stone, you can see steps formed by shadow just a few days past the fall equinox.

> The Temple of the Sun

As if two paeans to the sun were not enough, there is the semi-circular Temple of the Sun.

A trapezoidal window on the rounded wall (seen in the left hand photo below) is positioned to light up the large, central altar stone at the winter solstice. Another window lights the altar at the summer solstice.

In the photo on the right, the sun temple sits on the tiered tower structure in the middle ground on the left.

Anthropologists believe this temple served as the site of seasonal rituals as well as sacrifices to the gods. (Our guide assured us that routine rituals aimed at fertility of crops and so on involved sacrifice of llamas…however, on the rare occasions when the gods showed their anger through a catastrophic event, such as an earthquake or other deadly natural disaster, the most beautiful young girl would be selected as the most valuable offering. Eeeeks.)

Ollantaytambo, Peru 9/23

Between Machu Picchu and Cusco lies the Ollantaytambo archeological site. Maybe because its softer stone has been pelted by wind over the centuries, the temple of the sun here is less distinct and thus more mysterious in its design and use. But what is there is even more impressive in its monumental-ness than what we saw in Machu Picchu.

The temple’s main structure comprises 6 stone monoliths of staggering proportion.

On one, there are still visible etchings of the chakana, the Andean cross. On another there are outlines of 3 massive puma heads, representing the middle realm of present life.

We can only speculate on the content of other original images; it is possible they were never finished before the Spanish invasion.

The island of Maui

Just a couple of miles up the coast from our new home in South Maui is an ancient fish pond where a 1,100 foot wall of lava rock encircles a 3-acre expanse of shallow water. This pond and others around the Hawaiian islands were built centuries ago to trap fish near the shore.

While the rock wall appears at first to be shaped as a large semi-circle, a closer look shows that the north end begins as a straight line that runs about 75 yards out to sea before it begins to curve around. At the winter solstice, sundown occurs precisely in alignment with that straight wall.

Like their counterparts on other continents, ancient Hawaiians revered the life-giving sun, studied it, and marked its reliable passage.

Epilogue

The sun’s eternal flame: A sundial for modern times

A work trip to Kentucky sometime in the 1990’s included interviews at the state capitol. I decided to drive from Louisville to Frankfort so I could see the famous thoroughbred farms and blue grass up close. Seeing a small sign for a Vietnam veterans memorial, I made a spur-of-the-moment detour to visit it.

A few months earlier, I had visited the Vietnam Memorial Wall in Washington DC, where I found the name of a close family friend. A weight returned to my chest that day, as I recalled how, during that war, we pored over the lottery results in the newspaper with a list of beloved young men’s birthdays in our hands.

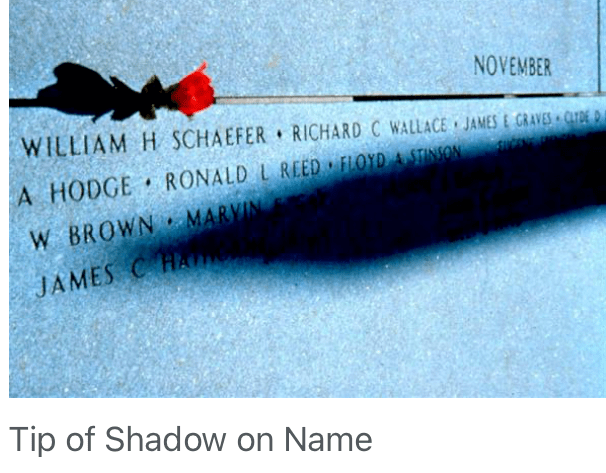

Approaching the Kentucky state memorial, I saw that it was a huge sundial.

Its base stretched many yards, and I could see lines and written words scattered in a formation I didn’t immediately understand.

As I walked around on the base I saw that the 12 months took the place of the 12 hours. Years were also etched into the dial—along with hundreds of names. Wondering how to read the meaning, I walked to where the shadow fell that afternoon. There I saw that the shadow’s tip touched a name—and I saw that the name was carved within a sector of the dial that marked a specific month and a year.

It dawned on me that this artist had designed a monument that used the inexorable movement of the sun’s shadow to mark the end of each soldier’s life.

Experiencing that monument put me in an altered state as I continued my journey past miles of white fences and long-legged horses grazing the thick bluegrass.

This sundial connects our present to the past of centuries ago—to our ancestors’ using their knowledge of the sun’s journey to mark the passage of seasons, and to express what that passage can mean for human lives.

Leave a comment